Stein, a math teacher, said he doesn’t think it makes sense to pull students off of computers entirely — state tests are all online now, and teaching statistics requires datasets stored on software — but many teachers agree there is too much screen time in class.

“The default is always just do it on the screen,” he said, “instead of thinking about, ‘Do we need to do that on the screen?’ I think that that’s the issue.”

The Montgomery County Council of Parent-Teacher Associations is pressing the district to provide a formal process to request “non-screen alternatives” for families that have “made the conscious effort to limit their children’s exposure to screens.”

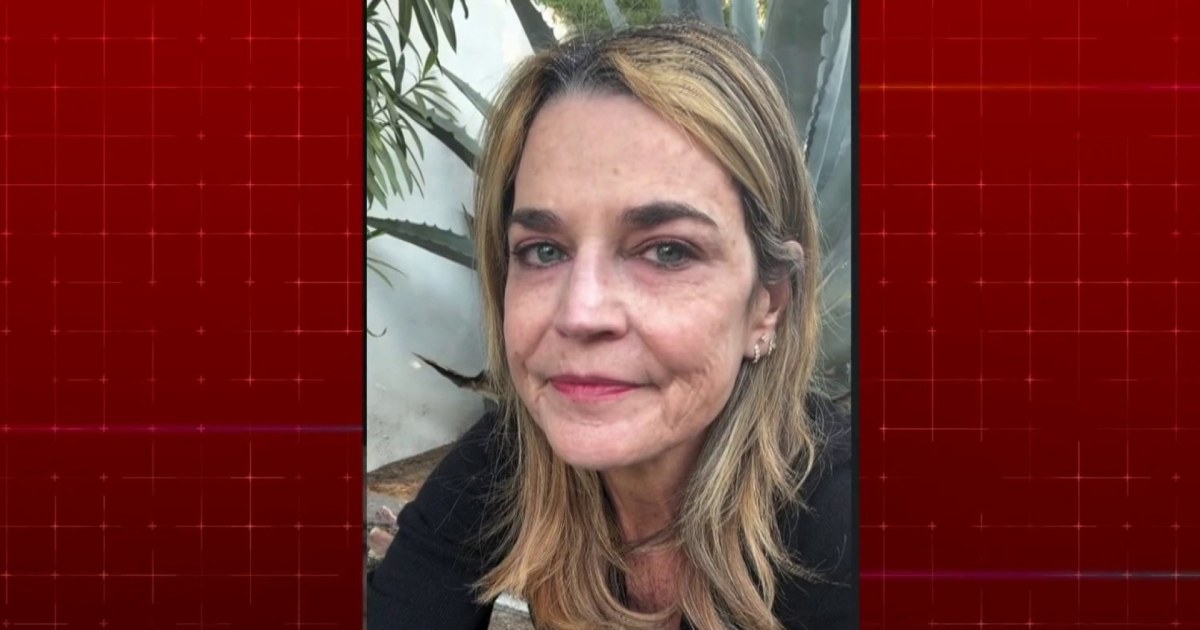

Lisa Cline, a Montgomery County mom who chaired a parent advisory committee focused on technology, said she opted her son out when he was in third grade and then requested each school year that his teachers keep him off screens as much as possible until he graduated high school last year. She said she hopes to work with the advocacy group Fairplay for Kids to launch a national campaign urging parents to opt out of school-issued devices.

“I think it’s a win, actually, if we get to that point where the default is you opt in,” Cline said.

Different strategies

Parents are typically asked to sign paperwork at enrollment granting consent for the schools to give their kids laptops. Nicki Petrossi said when she initially refused to sign it in 2024, the school district in Fullerton, California, told her that she was legally barred from doing so. According to a letter the district provided her, reviewed by NBC News, administrators argued state rules require children to use computers if that’s how the school is teaching a curriculum.

A spokesperson for the California Department of Education said “how a district implements the state-adopted standards is up to the district.” The district did not respond to a request for comment.

But Petrossi was certain she needed to get her children back on an analog education, in part because she’d already spoken to a dozen teachers from around the country about problems they had with devices in class for her podcast, “Scrolling 2 Death.” She also worried about recent large-scale hacking of education software. So last year, she transferred her children to a charter school that’s low-tech and uses a classical education curriculum.

“Once you know the background of why these devices were even pushed so hard, you know the data exposures that are happening,” she said, “then you know that our kids are the products and that teachers don’t even like it.”

Petrossi also co-founded the Tech-Safe Learning Coalition, which has posted templates that parents can send to their districts to limit their children’s use of school technology, so that “parents have more ammo to go to their schools and have these conversations,” she said.

Leave a Reply