Fifteen years of catching passes and returning punts in the NFL made DeSean Jackson an authority on running a route.

But last December, when Delaware State hired Jackson as its head football coach, he knew far less about running a practice or a budget because, to that point, his coaching résumé included all of one season assisting at a Los Angeles-area high school. The role didn’t prepare Jackson for the “million variables” he was soon addressing on campus in Delaware, such as helping players get to class, raise their grades, find housing and sign up for meal plans.

“As a head coach, man, there’s so many different things that I didn’t even realize took place,” Jackson told NBC News.

For decades, landing a head-coaching job in college football required climbing a career ladder that usually started as a low-ranking graduate assistant, then to a position coach, then a can’t-miss coordinator. Outliers were few.

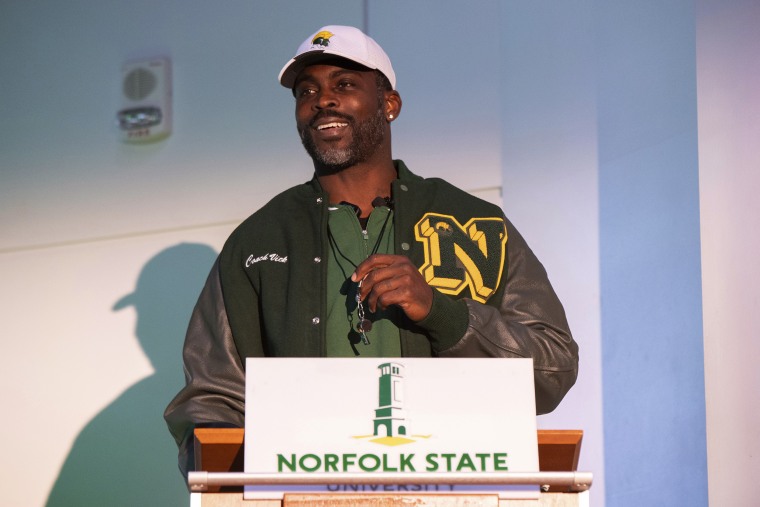

Yet in 2021, even though former NFL Hall of Fame running back Eddie George had never coached and initially was resistant to the idea, he was hired by Tennessee State, in the belief that his national name-brand credibility would energize potential players and donors and put its school on the map. Weeks before George’s hire, Alabama State named Eddie Robinson Jr., an alumnus who had played in the NFL before going into broadcasting, as its coach. And last winter, as former NFL star quarterback Michael Vick took over at Norfolk State, the teammate he used to throw passes to with the Philadelphia Eagles, Jackson, got the offer from Delaware State.

Amid the rapidly changing economics of college athletics, where football programs typically generate the lion’s share of an athletic department’s revenue, success or failure in such jobs has far-reaching implications. Judging who is best suited to run a program should be viewed through the criteria of not only how they would coach, but how they would act as a chief executive, George told NBC News.

“Just because you’re a play caller or position coach (and) you’ve been doing this for a long time doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re a great leader or head coach,” said George, who, after four seasons at Tennessee State, left this winter to coach Bowling Green State University after also interviewing with the NFL’s Chicago Bears. “I think that’s important. So you’re not necessarily looking for a football coach, you’re looking for a leader.”

When George and Jackson were mulling whether they could be that type of leader, they each called the one coach who they credit with starting the trend: Deion Sanders.

A Hall of Fame defensive back and returner who had largely worked as a television commentator in retirement, Sanders had spent a few years as a coordinator at Texas high schools, coaching his sons, when Jackson State hired him as coach in 2021. Overnight, the celebrity of a player nicknamed “Prime Time” thrust a historically Black college — just like Tennessee State, Delaware State, Norfolk State and Alabama State — that competed at the second-highest level in the NCAA pyramid into mainstream relevance.

In Sanders’s first season, nine games were played on ESPN networks, and Jackson State attracted sponsorship pledges from firms as large as Walmart and Gillette. Over his three seasons, Sanders brought in his sons, including Shedeur, the starting quarterback; stunned all of college football by signing the nation’s top recruit, Travis Hunter; and went 27-6, the best winning percentage of any coach in the school’s history.

In 2023, Sanders parlayed that success into a higher-profile opportunity at Colorado, where his teams have sold out a once-quiet stadium, produced a Heisman Trophy winner in Hunter, and been as much a fixture of the sport’s conversation as such powers as Alabama and Ohio State. (Colorado declined an interview request for Sanders.)

His experience has had a downstream effect on other coaches.

“I don’t think I would have been in this position without that,” Jackson said.

Though precedent for hiring a former player who had never coached before existed in leagues like the NBA and MLB, it wasn’t common in college football. Only four years before Coastal Carolina named Joe Moglia its head coach in 2012, he had been the chief executive of TD Ameritrade. But even that nontraditional hire had a traditional background, as Moglia had worked as a college assistant for more than a decade before beginning a career on Wall Street in the 1980s.

“It’s definitely made it a little more socially acceptable to maybe hire a guy like a Deion to say, ‘Hey, come run this, come run my program without previous head coaching experience,’” said Maryland coach Mike Locksley, the founder of the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches. “Because of the success he had there, (it) opened up the door for more opportunities, and to me, that’s Eddie George at Tennessee State having a chance at Bowling Green.”

“I think that this has created another pathway, because you hear a lot that there’s not enough coordinators or guys that have experience to be head coaches,” he continued. “Well, we’ve seen other sports take former players and the experience they got from playing would qualify them in terms of having some experience, because they’ve been around it at the highest level. It just gives us a whole nother pool of qualified people in the game of football to pull from.”

In a sport whose players are predominantly Black, but the head coaches are predominantly white, that candidate pool has historically been small. Although 57% of Division I players were nonwhite in 2012, the first year in which NCAA demographic data is available, just 20% of head coaches were nonwhite. In 2024, the share of nonwhite players had increased to 65%, while nonwhite coaches made up 23% of their ranks. Those figures include historically Black colleges and universities.

In the sport’s most powerful conferences, nonwhite players accounted for 66% of the roster spots last year, while nonwhite coaches accounted for 25%. In the last 12 years, Black head coaches have ranged from a low of just six (in 2012 and 2013) to a high of 10 (in 2020 and 2021).

Locksley had been a career assistant before New Mexico hired him in 2009. The experience did him little good. He went 2-26 before being fired midway through his third season.

“I was a failed head coach,” he said. “I often equate the first head coaching opportunity to the same as having your first child as a dad. You can read every baby book you want. You can have the room set up and but until that baby gets there, kicking, screaming and s—ing, you don’t really know, and you just start reacting.”

In 2020, Locksley founded his coaches association to equip minority coaches with better preparation. Through a program dubbed its “academy,” young coaches are paired with sitting athletic directors and power brokers to begin conversations about nuances of the top job — think budgets, media training and building “alignment” with a school’s athletic director, school president and board of trustees. The knowledge is helpful, but perhaps even more so is the relationship.

Although the NFL mandates that candidates of color must at least be interviewed for head coaching and coordinator openings, no such nationwide analogue exists within the NCAA, and knowing an administrator who can vouch on a coach’s behalf is critical, multiple coaches said. Representation is also slowly increasing in an athletic department’s corner office; last year, out of 67 athletic directors in the NCAA’s most powerful conferences, 10 were Black, double the number from 2013.

Of the 11 minority head coaches who have been hired since Locksley created his association, nine — including Notre Dame’s Marcus Freeman and Michigan’s Sherrone Moore — took part in the academy.

If Sanders opened the door for other nontraditional hires, whether the trend continues depends on their success. George tried to reduce his learning curve before his first season at Tennessee State by calling Sanders, who was coming off his first season at Jackson State, but it still took two seasons before George felt he understood all of the administrative, emotional and coaching components of the job. Last fall, Tennessee State made its first playoff appearance in nine years and won its first conference championship in 25 years.

Last winter, George called Sanders again while pursuing the job at Bowling Green, which is not a historically Black college and plays one level higher than Tennessee State on college football’s pyramid, to ask about how Sanders made the transition from Jackson State to Colorado.

“He’s been a very, very good resource for me on my path,” George said. “OK, show me the way. Where are the pitfalls at? Where are the blind spots?”

Now the scrutiny turns to Vick and Jackson. Their teams play on Oct. 30 in Philadelphia, where both were teammates with the Eagles. Their appointments have already brought mainstream media exposure; a docuseries will follow Vick and Norfolk State through the season.

“I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily ‘pressure,’” Jackson said. “You know, I do feel like it’s a lot riding on it.”

Regardless of a coach’s experience, what determines success is pivoting quickly and learning on the job, “which most of these guys who have played at the highest level, they have and are used to being able to figure things out pretty quickly,” Locksley said.

One argument for hiring a former NFL star who lacks coaching experience is that while they may not have spent much, if any, time on the sideline, they have direct access to “a Rolodex of guys,” as Jackson said, who have been successful in coaching. In a full-circle moment, Vick this offseason called George, he said, to ask many of the same questions George had asked Sanders only four years earlier.

Jackson, meanwhile, called Los Angeles Rams coach Sean McVay and coaches he played for in the NFL such as David Cully, Marty Mornhinweg and Andy Reid, the Super Bowl-winning coach of the Kansas City Chiefs, whom Jackson and Vick played for in Philadelphia.

Jackson wanted their honest opinions on his prospects (it helped his decision to hear, “‘You’ll be a hell of a coach,’” Jackson recalled) and to emulate how they related to players.

“The coaches that I respected the most are like the Andy Reids that was like second fathers to me,” Jackson said. “The biggest thing for me is where, man, I got an opportunity to help change these kids’ lives. I mean, if these young dudes want to make it to NFL, hey, it’s not guaranteed everybody will make it. But one thing you can do is you can give them the information, and, you know, hopefully they’ll take it into what it’s worth and apply it to their lives.”

Jackson also called Sanders. Accustomed to resource-rich NFL teams, Jackson wanted to know how at Jackson State he had navigated everything from providing for players on a tight budget at a historically Black university to managing relationships with his university president.

“Deion helped prepare me for those,” Jackson said, “and just kind of gave me advice and saying, ‘You know what, if you have these obstacles here, these are people that you could probably call and talk to to kind of help get you through that process.’”

Leave a Reply